Review: In Defense of Ska by Aaron Carnes

- Dillon Allen

- Jul 11, 2021

- 12 min read

This Simple, Beautiful Beat

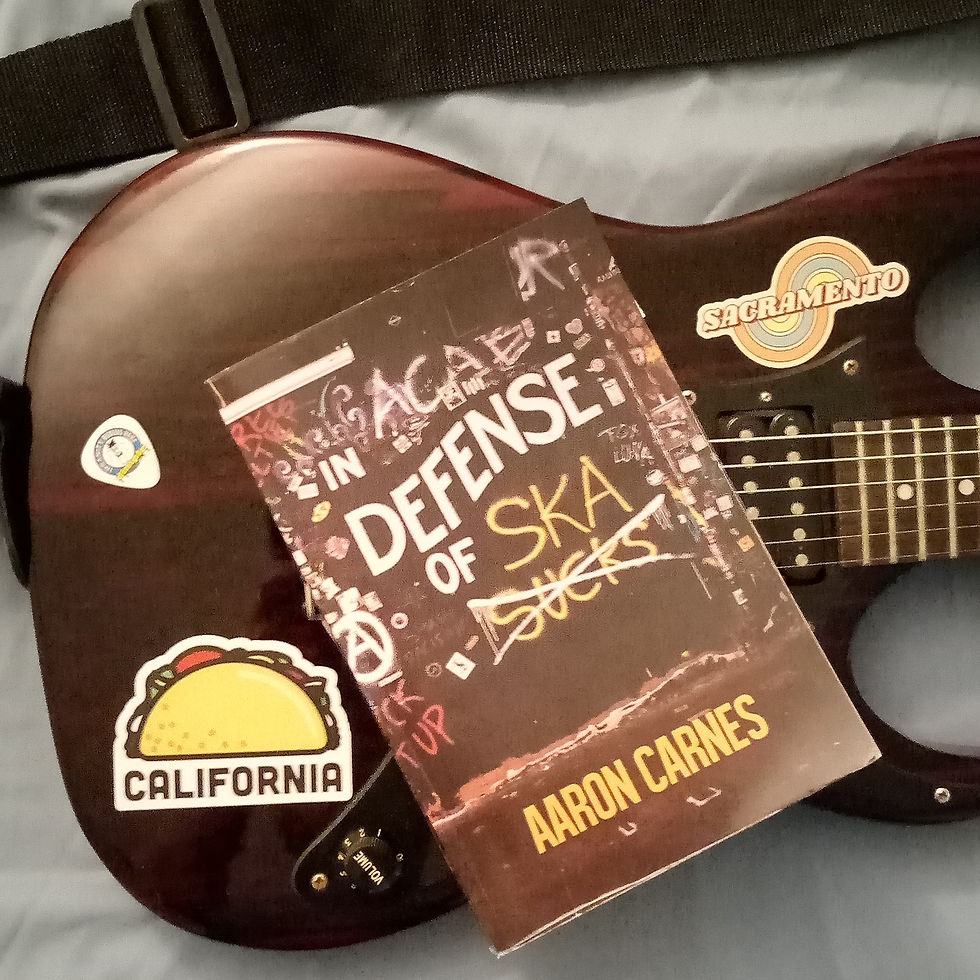

In Defense of Ska by Aaron Carnes

6.5/10

Did you know Oscar Isaac (Poe Dameron in Star Wars: The Force Awakens) used to be in a ska band? Did you know Brandon Flowers of the Killers once called out The Bravery for starting out as a ska band (and that this was supposed to be a huge diss)? Did Brandon Flowers know at the time that even the drummer of his own band was once in a ska band?

Ska originated in the ghettos of West Kingston, Jamaica during the 1950s. 2 Tone Ska was the resurface in England in the late 70s (with bands like The Specials, Madness, etc.). Then, the inaptly named "Third Wave" occurred in the mid-90s U.S. This "Third Wave" was really the continuation of the ska genre, or movement (or "way of life", as Carnes calls it). Ska music, and fans of the genre, never went away. The waves are only in reference to the relative surges in popularity in the culture—especially the mainstream. Although Carnes is clearly not a fan of the "wave" label, he predicts that if there is a current-day cresting in popularity that might soon be labelled the "Fourth Wave", it's happening in México.

About seven decades from the inception of the genre in Jamaica, Sacramento, California based music writer Aaron Carnes offers us this book of history, definition, nostalgia, reclamation, and praise. In Defense of Ska was published in 2021 by independent literary press Clash Books, who "put the lit in literary".

Aaron Carnes played drums in Flat Planet, a ska band from Gilroy, California that was active in the 90s. Other than being a ska band member himself back in the day, Carnes did his due journalistic research, interviewing many people from the ska and DIY punk scenes for the making of this book. He has authority of his own, but he also does a lot to give credit where credit is due. He gives credit and attention to particular artists, bands, promoters, venues, and fans. Another example is that Carnes highlights the importance of some early ska compilations, in the 90s ska-punk scene especially. "A lot of people think that it was Tony Hawk that did a lot for us," says The Suicide Machines’ Jason Navarro. "Misfits of Ska, that shit put us on the map." Misfits of Ska was one of these ska compilations, released in 1997.

The foreword by the legendary (in my book [& in this one]) Jeff Rosenstock is straight-forward, in-your-face, romantic, and positive as hell. Here's what he has to say about Carnes' Defense of Ska: "It's like no other music history retrospective I've ever read. It holds nothing but ska—the most disregarded genre of music—in regard. And it doesn't hold back any punches."

The book is made up of twenty-seven chapters. One of those, titled "Ska is Dead", goes over Rosenstock's own upholding of ska tradition, as well as his progressive punk pushing of it into the future. Rosenstock is known from bands like the Arrogant Sons of Bitches and "schizophrenic cult punk band" Bomb The Music Industry!. BtMI! (which is not a medical abbreviation for Bowel to Mouth Infection! but the way that I’m abbreviating that second band) gave away their music for free on the internet in the early 2000s, right before Radiohead made that practice "cool" with their 2007 release of the album In Rainbows. In the 2010s, Jeff Rosenstock put out a string of great solo records: 2012's I Look Like Shit, 2015's We Cool?, 2016's WORRY., and 2018's POST-. Starting off the new decade, Rosenstock put out NO DREAM in 2020, then reimagined the whole album as a ska album in 2021. He literally redid the whole record—a song-for-song ska reworking of each individual track. In my opinion, it made the album a lot better. I was legitimately surprised by how much more I liked SKA DREAM compared to NO DREAM. After all, it's the same songs lurking underneath, right? That's the transformative power of ska I suppose. The new decade just might bring us some great things in the ska department. Rosenstock is an inspired choice and a fitting figure-head for forewording Carnes' Defense of Ska.

On that note, let’s get back to the book.

The weirdest thing about how In Defense of Ska is written is the content's dissonance with its title. It is a defense of the merits and influence of the genre in many ways, but it's not written for the people attacking ska. It's not written for people who don't know much about ska but avoid the genre because they overhear the undeserved hate it gets throughout the culture. No, In Defense of Ska is written for ska fans. It's written for people who already enjoy it and people who may already be defending it. In this way, I think the book misses its aim.

Or, maybe it's supposed to lend some more information to ska fans who want persuasive evidence to use in their own arguments in defense of ska. If this is the aim of the book, it does a better job in that regard. It's still not great though. Many passages in Carnes' book, especially in the middle area, are more nostalgic (especially for ska insiders) than informative, persuasive, or even classifiable as an argument. Still, if an open-minded reader picks up this book while knowing little to nothing about ska music going into it, they will probably learn a good amount. Plus, nostalgic stories are fun to read, at times. As a ska fan myself—with admittedly low knowledge of the genre’s full history going into this book—I enjoyed reading In Defense of Ska. What bothers me most about the content’s dissonance with the title, though, is that I doubt anyone who dislikes ska will be compelled to pick up this book. And, if they do, I don’t believe they’ll walk away from this reading experience with a changed mind.

I liked this book. I enjoyed reading it—as I’ve said. I desperately wanted to rate it higher. Near the beginning of my reading experience, I thought it was great and would continue to be great. Even after finishing it, I originally gave it a 7/10. But, honestly, I can’t rate it in the 7-or-higher range with a clean conscience. I’m a pretty generous, forgiving rater most of the time, and I wanted to be especially nice with Carnes’ book because I appreciate the focus of the project and much of the content. However, there are issues beyond the defense missing its aims.

I take issue with how the chapters are organized. The timeline jumps all over the place, forward and back and back forward again. It’s jarring and weird. It’s needlessly confusing. It makes it less of a page-turner. I don’t see why this overview of ska couldn’t have been presented chronologically. It would have been so simple and logical to read through. It starts off great with the Rosenstock foreword, then a chapter called “First Things First . . .” in which Carnes introduces himself and the topic of the book. He establishes his authority as a music writer and a former drummer of a ska band. In this section he states a hopeful outcome of his book:

“Hopefully, this book will challenge your pre-conceived stereotypes about ska. If nothing else, I hope you can read it with an open mind and realize that you don’t know jack about the genre you confidently hate. Maybe you’ll even learn a few things in the process. Who knows, maybe you’ll even give ska a chance.”

This goes back to my earlier issue with the book not appealing to that intended audience. I highly doubt anyone that confidently hates ska is going to pick up a book called In Defense of Ska (unless they misinterpret the artwork on the cover to read IN DEFENSE OF SKA SUCKS—ignoring the “SUCKS” part being x-ed out by spray paint and therefore thinking the book is a defense of the argument that ska does, in fact, suck).

Anyway, let’s get back to the organization issue. The first chapter after these two introductory sections is titled “A Very Brief History of Ska”. I really appreciated this chapter, but it also made me expect the rest of the book to move in chronological order, from the ghettos of Jamaica in the 1950s to today. It does not move in chronological order at all. Right after this very brief history, the chapters bounce all over the place in terms of time, location, and topic. Perhaps Carnes was trying to make the reader feel the disorientation felt while skanking around in a sweaty mosh pit at a ska-punk show. That’s an interesting idea in theory, but it’s not fun to read.

Carnes does write in his introduction that In Defense of Ska “is not by any means a complete history of ska. I make no claim to give every key ska musician a voice or to tell a complete story of ska’s evolution over a specific set time frame. This book explores what it means to love ska—the most maligned genre of music that everyone else hates with a passion. Ska fans deserve a seat at the big kids table alongside punk, metal, jazz, hip-hop and alternative rock.” [Note: The lack of an Oxford comma here is Carnes’ choice—not mine]. So, the author is not attempting to provide a complete history. I actually think he does a great job interviewing a variety of people and telling diverse stories in good detail. Still, there’s no reason he couldn’t have written an incomplete history of ska that’s presented in a chronological order.

Moving on to the next big issue with In Defense of Ska: there is an egregious amount of typos. One benefit of publishing with an independent literary press is that you have more freedom to write about niche topics that traditional publishers would avoid (such as a whole book on ska). You may also have more freedom to write in a unique and/or experimental style. One drawback, however, is that you may not have an editor. I don’t know if In Defense of Ska had an editor or not. I don’t see anyone given credit as an editor anywhere in the book. If there was an editor, they should not put this book on their résumé, and they should be grateful that they are not credited as an editor in the opening pages. Seriously, there is an egregious amount of typos.

On page 94: “Ackermann’s favorite meme he ever created is a picture of philosopher Socrates with Operation Ivy’s lyrics for ‘Knowledge,’ which is a few words different that Socrates’ famous quote.”

On page 113, the same exact sentence is printed twice in a row: “He also brought in out of town bands like Phoenix’s underrated ska band X-Streams. He also brought in out of town bands like Phoenix’s underrated ska band X-Streams.”

On page 119, legendary New York Punk venue CBGB is spelled two different ways: “CBGBs had hardcore matinees on Sundays, which did well because, unlike evening shows, matinees were for kids (i.e., all-ages). Hingley thought CGBGs might be where the strewn about bands playing ska could coalesce and flourish.”

On page 123: “Nether The Toasters nor Bim Skala Bim got paid royalties for their albums.”

On page 179: “Lead singer Dan Vitale told them they could use it for free as long as they gave them credit and didn’t forgot them if they ever hit the big time.”

On page 209, a paragraph begins: “Mods originally were a ’60s subculture linked to stylish garage-rock bands like The Who and Small Faces as well as, and copious drug use.” This paragraph continues for another five sentences until we reach the bottom of the page. The top two-thirds of page 210 are taken up by some photos. Then a weird printing/formatting error appears. Below the caption to the photos, part of a previous sentence is reprinted: “Mods originally were a ’60s subculture linked to stylish”—then that line ends without any punctuation or anything and the real next paragraph begins right below that. “L.A. had the biggest mod scene of the U.S. . . .”

On page 230: “One of his most emotionally impactful song is ‘Melbourne’ from his 2012 solo album Around the Word.” [I didn’t catch this in my initial reading, but looking it up now, I see that the actual title of Dan Potthast’s 2012 solo album is Around the World.]

In the chapter “Nancy Reagan”, the group that wrote the song titled “Nancy Reagan” is once spelled “Blue Riddum Band” and then spelled “Blue Riddim Band” right there on the same page. This happens on page 232, and then again on page 235, when it’s spelled “Riddim” first and then “Riddum” in the following paragraph. In this same chapter, Bob Marley is given the same treatment: “Reggae was a cult form of music with Marley a modest figure in the ’70s. Reggae would cross-over into the mainstream in the mid-80s. Marely gained megastar status at the release of his retrospective, Legend, in 1984, three years after his death.”

On page 263: “I wanted to know more about Butler’s ska past, so he and I spoke on the phone a year-and-a half after he messaged me to go further go down the ska rabbit-hole.” [In my initial reading, I only underlined the “to go further go” part, but typing out this whole sentence now makes me realize how strange of a choice it was to write “a year-and-a half” like that. The built-in Typo-Finder of Google Docs agrees with me. It puts a jagged blue line beneath “year-and-a half”. When you hover over it, the suggested revision is “year-and-a-half”. I personally think it would be fine without any hyphens at all. It could be “a year and a half after” and that would be perfectly clear. This isn’t a huge one. I just thought this was interesting to note. Sub-note: I’m imagining this is the point where some readers of this review, if they’ve made it this far, will be rolling their eyes at what I consider “interesting to note”. This might be the last critical straw where they decide to stop reading.]

On page 279: “The audience members came from the nearby East LA, South Gate, South Central, Boyle Heights, Inglewood and Lynwood neighborhoods, and well as Santa Ana, Inland Empire, and the San Fernando Valley.” [Another thing I’m noticing now is that Carnes abbreviated Los Angeles as “L.A.” earlier and as “LA” here.]

There might be more typos than this. If you find any other mistakes within the pages of In Defense of Ska, send me a message. I will add it to this list, and you will earn a grateful reply from me. Also, if you find any typos in this review, feel free to let me know. This review has no editor.

As I said before, I’m usually a generous, forgiving rater. Writing teachers and tutors where I work generally refer to typos as “lower-order concerns”, and I agree with that. But this book pushes my limits. Typing mistakes are lower-order concerns in early drafts, because that’s when you’re still trying to figure out the big picture stuff: What do I want to write about? How should I narrow my focus? Should I keep this paragraph or cut it out entirely? Should I organize my chapters chronologically? Typing mistakes are lower-order concerns in early drafts because they can be edited later. You can edit out typing mistakes when you’re finalizing things for publication. It’s not that typos and organization issues are unforgivable. The problem is that In Defense of Ska feels like an early draft of a book that could be great.

Interchangeably misspelling Bob Marley’s surname seems like the worst offense to me. It’s annoying when someone misspells your name in an e-mail exchange, especially when it’s right there. Publishing “Marely” in a book, in a sentence about the album released after his death, feels the most disrespectful. Not only that, but these errors, all added together, make the book feel disrespectful to the reader. That probably sounds dramatic, but it does sort of feel that way, doesn’t it?

By now, it probably seems like I’m tearing this book to shreds. You might be imagining me setting the shreds of this book on fire after I wrote down all the typos I could find. That’s not my intention in this review. My copy of In Defense of Ska is still intact. I’ll say it again. I liked this book. I enjoyed reading it. For me, a 6/10 means “It has something to offer” and a 7/10 means “It’s good”. In Defense of Ska is really close to being solidly good. It could have been pretty damn good with an editor, and, if that editor suggested some re-organizing as well, it could have been great!

It’s cool to have a book like this that’s all about ska—just like what Rosenstock wrote. The passion, romance, and fun is all there on the page. Huge props to Aaron Carnes for that. I truly appreciate what he did here with this book. Call me a stuck-up English teacher if you want, but I wish this book was written more seriously, to balance out the raw, spastic passion.

Since I am a stuck-up English teacher, let me highlight another quote here that I took issue with. It might explain some philosophical lack of seriousness. This is from the conclusion of the chapter “So Far Away”, in reference to the band Skankin’ Pickle’s merch guy Kevin Dill, who is fond of pranks:

“Kevin saw everything as a joke. His perspective on life blurred the lines between comedy and tragedy into one, big, ridiculous gray mess. He intrinsically understood that to take anything serious was a waste because life was a joke, and our death was the bitter punchline. Sometimes I think that Kevin’s the only person in the world that’s got it all figured out.”

I disagree with this fatalistic philosophy. It feels like a cop-out for complacency. There’s no hope or optimism in this quote. There’s an avoidance of taking anything seriously, which feels like an avoidance of sincere feelings and even social responsibility. Why write a book at all, or make music, or contribute to a culture in any way if all of life is a joke and we basically have no free will? Alright, I get that I’m reading too far into it. Let’s wrap this thing up.

I learned a good amount about ska in this book, and I discovered some bands that I still need to take time with, digging through their discographies, and likely grooving to a lot of great music. I do believe that ska has merit and cultural value. There’s a lot of great music under the ska genre umbrella that is not only fun to listen to but also infectiously positive, sociopolitically critical, hopeful of a better future, and unapologetically sincere.

Why is ska so enduring and popular for sometimes small but consistent groups of passionate people in cultures all over the globe? In Carnes' own words, "it really boils down to a willingness to love music that moves you, and to not care about what other people think." Although I think Carnes could have cared about the reader more while drafting In Defense of Ska, I really like his sincerity here at the end of the book.

Comments